Woburn Plantation Manor House Remains, Burwell Family Cemetery, & Nearby Site of Former Woburn Winery

Hours:

Private properties not open to the public.

Locations: The Woburn Plantation Manor House Remains & Burwell Cemetery are in the vicinity of coordinates 36.542702, -78.463798, accessible via a gravel road that intersects with Ivy Hill Road just south of the Virginia/North Carolina line; the manor house remains include a foundation and chimney, to the east of the gravel road and the Burwell Cemetery to the west.

Former Woburn Winery's site is in the vicinity of 1516 Ivy Hill Road, Clarksville, Virginia. [map]

Woburn Plantation, originally home to Armistead Burwell (1770-1820) and his wife, Lucy Crawley Burwell (1775-1825), was completed circa 1799. The related Woburn property eventually totaled over 1,000 acres in the fertile lowlands of Island Creek. Craftsmen Jacob Shelor (after 1753-around 1840), a stone mason, and John Inge (1748-1820), a carpenter, were employed to build the house. Inge was recommended to Burwell by his brother-in-law, John Stark Ravenscroft (1772-1830), who was the first Episcopal Bishop of North Carolina, serving from 1823 to 1830. Shelor and Inge separately and collectively worked on Elm Hill and Prestwould, Mecklenburg County homes of the prominent Skipwith family, and on Spring Bank (also known as Ravenscroft), the Lunenburg County home the aforementioned John Stark Ravenscroft and his wife Anne Spotswood Burwell (1773-1814), sister of Woburn's first Armistead Burwell. According to page 74 of The Burwells of Kingsmill & Stoneland: An Account of An American Family 1633-1900 by Burwell descendent Robert Andrew Parker, "... the house was a two-story frame structure joined at one end to an existing story-and-a-half cottage. The main block, with a hip roof and large front porch which extended the length of the house, was similar to the main block of Ravenscroft. Eventually, the main house was flanked in front by twin story-and-a-half office/school dependencies. Years later, another addition to the original cottage provided an interior kitchen on the first floor and enlarged the bedroom upstairs."

Nearby Burwell Cemetery includes internments for its first owners, Armistead and Lucy, along with their grandsons, Confederate soldiers Charles Sturdivant Burwell, C.S.A., Company E, 14th Virginia Infantry Clarksville Blues (1842-1864), William Hunt Burwell (1847-1866), and Armistead Burwell (1840-1920). The latter was the grandson and namesake of the first Woburn owner; he enlisted in Company E., 14th Virginia Regiment ("Clarksville Blues"), and served off and on because of illness, until injured in battle at Drewry's Bluff on May 16, 1864 with an extensive gunshot wound of the left thigh. After convalescence, he was employed as a nurse near the end of the war at General Hospital No. 1 in Kittrell Springs, North Carolina. He was paroled May 14, 1865, and in September 1865, he was sent as a delegate from St. Luke's Church to the Episcopal Council. In his last will and testament, Confederate veteran Armistead Burwell stated his desire "to be buried in the family burying ground, and as soon thereafter as may be convenient my executors shall cause to be erected over my grave a neat marble tombstone with such inscription as they think proper and underneath said inscription the words, 'A Confederate Soldier' ...."

Woburn's first Armistead was the grandson of another Armistead Burwell (1718-1754), a Williamsburg merchant, who, upon acquiring much land, primarily through a patent in what is now Lunenburg and Mecklenburg Counties, became Southside Virginia's first Burwell by that name. Woburn's first Armistead was also the eldest son of Colonel Lewis Burwell (1745-1800), who commanded a regiment in the Revolutionary War and served 14 years as a member of the Virginia Legislature, and Anne Spotswood Burwell (1752-1789), granddaughter of Alexander Spotswood (circa 1676-1740), Lieutenant Governor/Acting British Colonial Governor of Virginia. The Burwells (pronounced "Burls" by many) were among the First Families of Virginia in the Colony of Virginia.

Famous Tidewater Burwell plantations include Kingsmill and Carter's Grove near Williamsburg. Burwell plantations in Mecklenburg County include Stoneland, near Finneywood Creek, north of Chase City, and Woburn, south of Clarksville near Ivy Hill. The Stoneland "complex", where Woburn's first owner, Armistead Burwell, was raised, included a grist mill, general store, iron mines and a forge, a saw mill, orchards, pastures, a still house, and hundreds of acres of productive tobacco and grain field worked by as many as 200 slaves. In order to ensure the classical education of the Burwell children, a boarding school was established at Stoneland where John A. Fowlkes taught English, French, Latin, arithmetic, and writing. The Stoneland house was destroyed by a fire on New Year's Eve 1815 with the loss of eight lives; Stoneland was then rebuilt on a smaller scale.

Woburn is referenced on page 211 of Susan Bracey's Life by the Roaring Roanoke in a section about a major new road, planned in 1811, which "crossed Eastlands Creek and went to Taylors Ferry"; at the south landing of the ferry, "the new road followed an established road to the right ..., crossed Island Creek, and met the North Carolina line opposite the home of Captain Armistead Burwell." Today Island Creek Reservoir and Island Creek Park/Public Use Area are in the vicinity of Woburn Plantation's remains.

Woburn's first Armistead died there in 1820; his will named his brothers Spotswood (1785-1855) and Lewis (1779-1847) along with their friend William Taylor as executors, plus Armistead's wife, Lucy as executrix. This Armistead's survivors included Lucy, their seven daughters, and an only son, John Armistead, then only seven years old. According to page 84 of Parker's book: "As executrix, Lucy took control of the estate and the operation of Woburn, which by then totaled two thousand acres in Virginia and North Carolina. In that day and time it was unusual for a lady to take such an active role in business affairs. Yet Lucy seems to have been equal to the task with advice and assistance from the executors, particularly from Spotswood."

Upon Lucy's death in 1825, Spotswood and his wife, Mary Green Marshall Burwell (1792-1856) were, according to Parker's book on pages 85 to 86, "... confronted with the additional responsibility of helping care for Armistead and Lucy's minor children. ... Now Spotswood, as Armistead's chief executor, would have to take on the day-to-day management of Woburn. Even before this, he had grown tired of trying to assist Lucy from his home in Granville, so he concluded that the most sensible approach would be to rent Woburn from Armistead's estate and move there until Armistead's only son, John Armistead, came of age and was able to take over. With some reluctance, Spotswood and Mary sold part of their North Carolina property to Mary's sister, Elizabeth Blackwell, hired out a number of their slaves in Granville, and consolidated the two families at Woburn. Although most of the children were away at boarding school, the Woburn manor must have been barely adequate to accommodate both families. In fact, during the last four months of Lucy's life, a sizable addition to the house had been constructed probably in anticipation of the Spotswood Burwells' move there."

Parker adds on page 90 that Spotswood "... became interested in gold mining as an alternate use of his resources, since farm commodity prices were depressed. A number of his planter friends in the Mecklenburg and Granville County area were enjoying some success at it. ... And so, he decided to gamble himself." On page 91 Parker continues: "The gold mining venture was organized by Spotswood in 1831 and managed by his oldest son William Armistead, then twenty-two years old. The other investor in the business was a friend and neighbor, John Y. Taylor. Mining equipment and supplies were purchased, and scores of Spotswood's slaves were dispatched from Woburn and his Granville County farms under William Armistead's supervision to the Bracket Mine on New Creek near Morganton, Burke County, North Carolina." The trip from Woburn to the mines took about three days. Parker continues on pages 91: "William Armistead's personal waiting man, 'Sweet Pig,' and his cook, Aggy, were among the slaves brought there from Woburn." Referring to Sweet Pig and Aggy as "favorites within the family", Parker explains on page 92 that Aggy, born at Stoneland, was in charge of the food preparation for all the slaves at the mines. Parker continues on page 92, noting: "Spotswood cautioned William Armistead about controlling food purchases, since he realized that the slaves would complain a good deal no matter what or how much they were fed in this unusual environment. He also wanted to insure William Armistead kept a tight rein on other expenses." Parker also indicates on page 92 that while Spotswood "... demonstrated great trust in his eldest son, ... he was the real decision-maker", writing his son three and four page letters twice a month, giving detailed instructions and lengthy advice.

Spotswood's letters to William Armistead also indicate some of his frustrations at Woburn. Parker notes on page 92: "At the time, Spotswood was forty-seven years old and had become partially crippled by arthritis. He had for seven years been bound up in the management of Woburn, of his own plantations and in the unpleasant problems of his father's estate, and he was tired of it all. He wrote William Armistead that farming did not suit him at all unless he was 'better able to attend to it.' He was totally frustrated that his frailty did not allow him to be as active as his mind, and he was uncomfortable living most of the time at Woburn, a place that he was only renting. All of these pressures prompted him to write William Armistead that if he could not make money at gold mining he was 'free to sell every negro I have at the minds [sic] and I have sent you a list of ages and prices.' In another letter he said that he had a 'serious notion of turning the whole of my estate into money'." Parker adds on pages 92 and 93 that Spotswood was a "compassionate master", ... trapped in a financial system that created both an economic and moral dilemma for him. If he sold ... (slaves) ... to a speculator what kind of treatment would they receive? If he freed them he would be ruined financially, and how would he care for his family? Yet he knew that slavery could not be justified on moral grounds. All of these thoughts must have pressed on him, particularly during the time of the Nat Turner insurrection in nearby Southampton County which occurred the year before he started the gold mining venture."

On page 93 Parker elaborates on the impact of what is commonly referred to as Nat Turner's Rebellion: "That rebellion had spread fear through the entire region since slave owners in Mecklenburg ... recognized that slaves comprised over 60% of the population there. Slaves living along the Roanoke in the area were 'sufficiently contiguous to asemble [sic] in bodies of 4 to 500 in a few hours.' Parker notes that as a result of the rebellion, the future of slavery was the topic of a two-week public debate in the House of Delegates with many legislators agreeing to discuss gradual emancipation. Parker notes on page 93 that Mecklenburg's representative, William Goode, "... opposed even the discussion of emancipation ...." Parker references this context on page 93: "In this environment Spotswood wrote to William about two of his slaves who were 'trouble makers' and had been packed off to the mines. Spotswood said, 'If they are not submissive and complyable (sic) to your orders you may dispose of them. However, I rather you not ...'." Parker elaborates on Spotswood's concern for his slaves, noting on pages 93 and 94 that in nearly every letter he "gave explicit instructions on how kindly he wished them to be treated"; Parker includes examples like Spotswood's asking William to give slaves money now and then, his asking him to "tell Jacob that his lady is still single", "Aggy that her children are growing and are sleeping in the house with us ...", and to "tell all the negros Howdy." Parker shares on page 94 that Spotswood's wife, Mary Marshall, sent sweet cakes and other treats to the Woburn slaves, working in the mines, while Spotswood sent part of the profits from the production of plantation pork to "Old Edmund". Parker adds on page 94: "In short, these were not patronizing gestures to keep everybody happy, but instead demonstrated that Spotswood cared for his slaves as people. Quite simply, he found himself caught in an inherited system which he did not relish."

While Parker shares the affection that Spotswood had for slaves like Old Edmund, Aggy, and Sweet Pig, he also indicates on page 94 that "Spotswood could be a firm disciplinarian." Parker continues on page 94, referring to a slave named Tom, who reportedly "had been caught stealing from another of the slaves" and was known as a "troublemaker" and described by Spotswood as a "great rascal", having tried to run away from Woburn twice. Parker notes on page 94 that during the second attempt, Spotswood directed his son Lewis Dandridge Burwell (1813-1874) to "prevent it by force, if necessary, and as a result, Tom was temporarily immobilized by a superficial gunshot wound." Parker notes that after Tom recovered, he was sent to the gold mines with instructions "to sell him if he caused further trouble." Also on page 94, Parker tells of Tom stealing a vial of gold, with which he bought a "forged pass from a Mr. Griffin, who ran a grog shop in Brindleton." Parker continues on page 94: "But Tom did not know what to do with his freedom and, after about two weeks of dodging authorities, he somehow found his way back to Woburn where Spotswood prevailed on him to tell the truth about his escape." Parker also notes on pages 94 and 95 that Spotswood's overseer, a Mr. Twitchel, found in Tom's quarters at Woburn what was left of the pass; this was sent to William Armistead with "careful instructions" on getting a confession and $50 in damages from Griffin. Parker notes that records do not indicate what William did exactly. Parker adds on page 95 that Tom was "not physically punished because he told the truth, but rather was confined until Spotswood could either arrange a sale for him to speculators or somehow get him to change his ways." Parker suggests that Spotswood was "... more concerned with settling accounts with Griffin who had broken the law and tampered with his pocketbook than with dealing with the errant slave whose truthful confession he admired."

As for the Burwell gold mining operation, it was closed down by 1834, due to a shortage of mechanized equipment, difficulties in shipping, cold winters, and fluctuating gold prices. Parker notes on page 96 that prices for tobacco, however, were at an all time high, and so slaves were brought back to Woburn to "crop tobacco". He also notes that in the meantime, Spotswood planned his family's return to North Carolina, buying a 1,086-acre plantation and mansion home, "Spring Grove", in Granville County, North Carolina; it was there that Spotswood and his family spent Christmas 1833. This came on the heels of John Armistead Burwell (1813-1857), Spotswood's nephew and son of Armistead Burwell and Lucy Crawley Burwell, marrying in June 1833 Lucy Penn Guy (1814-1859), and taking over the operation of Woburn, keeping a tradition of "Armisteads" and "Lucys" at Woburn. According to page 122 of Parker's book, John Armistead's cousin Lewis Dandridge Burwell advised his brother Robert Randolph Burwell (1829-1892), the youngest of Spotswood's children, that "Cousin John of Woburn" was among the "best planters in the section", to be visited by Robert and used "as a pattern". Eventually, aforementioned Confederate soldier Armistead Burwell, son of John Armistead Burwell and Lucy Penn Guy Burwell, and grandson of Woburn's first Armistead Burwell, became Woburn's owner, operating it into the early 20th Century.

In the 1980s the original story-and-a-half portion of Woburn Plantation's manor house was disassembled and moved to Franklin County, North Carolina, and reassembled for use as a guest house. Now what remains in Mecklenburg of the old manor house, also referred to as "the big house", is a stone foundation and chimney, complete with two stories of fireplace openings.

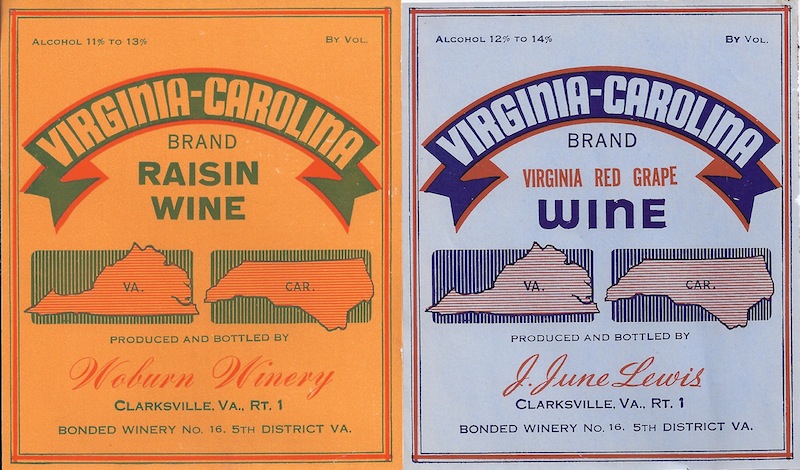

There is an old house, still standing at 1516 Ivy Hill Road. Referred to as "the little house", it was a Burwell family tenant house, associated with the remarkable and little known, Woburn Winery, operated between the 1940s and 1970s in the Ivy Hill area of Mecklenburg County on what had been Burwell family land. Owned and operated by John June Lewis, Sr. (1894-1974), Woburn is thought to have been the only Virginia winery by the early 1970s to manufacture wine solely from its own grapes, and the only winery to be owned by an African American in the country. Lewis had ties to the Burwell family, being listed on the 1910 United States Federal Census as a 17-year-old mulatto servant with the occupation of farm laborer, living in the household of the Confederate veteran, Armistead Burwell, then age 70. Lewis is listed on his U.S. World War I Draft Registration Card as employed by A. Burwell in the occupation of farming and manufacturing lumber for contract. A veteran of World War I, Lewis gained a heightened appreciation for viticulture and viniculture in 1919 while serving in the American Army of Occupation in the Rhine Valley of Europe. Upon his return home, he worked in the lumber business and is listed on the 1920 U.S. Federal Census as a "hired man", affiliated with the occupation of "saw mill" in the household of Armistead Burwell, age 79. Eventually, Lewis was deeded land by Armistead Burwell--a farm, land owned previously by the Burwells, and began growing 10 acres of wine grapes in 1933--almost immediately following Prohibition's repeal. Lewis opened his winery in 1940 with a storage capacity of 5,000 gallons, and produced Labrusca and hybrid wines. Known as the "Virginia-Carolina Brand", Lewis' products were listed as table and dessert wines in the Wines & Vines Annual Directory, Issue 1960. Wine writer Leon Adams attested that Lewis' wines were "sound" and carefully used yeast cultures from California.

Lewis' son, John June "Duckie" Lewis, Jr. (1930-), indicates that his father was born in "the big house" and first learned wine making as a child from Confederate veteran Armistead Burwell, whom the younger Lewis refers to as his paternal grandfather. He refers to his paternal grandmother as Anna Lewis, later known as Anna Lewis Dodson (1873-1939), who is listed in both the 1890 and 1900 Census as a black female, in the household of her mother, Winnie--also known as Winney--Lewis (1835-1937) with the addition of Anna's occupation as "farmer" plus the listing of her son John as a black male in the latter. Several public family trees on Ancestry.com support this lineage, linking intimately the Burwell and Lewis families.

Contributor: Leigh Lambert, Director of Southside Regional Library

(c) Copyright 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by Jason Winter ||