Mecklenburg County Courthouse & Confederate Monument on Courthouse Square

*National Register of Historic Places

393 Washington Street, Boydton, Virginia 23917

(434) 738-6191

Clerk's Office Hours:

Monday-Friday, 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM

Mecklenburg County Courthouse is located in the heart of Boydton and currently houses the 10th Judicial Circuit of Virginia. After an extensive 10.7 million dollar renovation and expansion, it was re-dedicated with a ceremony on October 23, 2011. This Palladian courthouse was constructed between 1838 and 1842 by William A. Howard and James Whitice, using Thomas Jefferson's architectural principles. It was constructed to replace the eighteenth-century courthouse and 1815 clerk's office. Bricks from the floor and walls of the original clerk's office were used for the walkways in front of the new courthouse. Howard and Whitice constructed the two-story, six-columned building at a cost of $8,000 with local brick and built the columns out of brick, covered with stucco, replete with entasis (the application of a convex curve to a surface for aesthetic purposes), as Thomas Jefferson's builders had often done.

(434) 738-6191

Clerk's Office Hours:

Monday-Friday, 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM

Of the various Jeffersonian-style courthouses in central Virginia, the Mecklenburg courthouse is unique with its six-column pedimented portico. All the other courthouses have only four columns. Charles Brownell, Ph. D., refers to the Mecklenburg County Courthouse's "imposing hexastyle or six-column Ionic portico" as the "grand finale" to Howard's career. Brownell also indicates that this courthouse was "Howard's last word on civic architecture" with the "essential Jeffersonian constituents ... in place: durable construction and a display of the Orders on a Temple Revival enframement holding an apsed, galleried, longitudinal courtroom." Brownell elaborates that the courthouse "lost its apse in the reworking of the interior." Brownell also notes that the Mecklenburg Courthouse "stands in the centerline of development", explaining that "central features include the portico floor, which lies only one step above ground level; the bell, which has no place to hang but the front wall; and above all else, the original color contrast. For during most of its history, the courthouse exterior consisted of red brick with contrasting pale trim of wood and dressed stone."

The brick building is laid in Flemish bond brick on the front and three-course American bond with Flemish variation on the sides. In 1950 following an addition to the rear of the building, all of the masonry was painted white. Now the structure presents a more monumental aspect than it did originally and bears a striking resemblance to the Virginia State Capitol (before its wings were added), designed by Thomas Jefferson. John O. and Margaret T. Peters, in Virginia's Historic Courthouses, declare: "No Virginia courthouse bears a closer resemblance to Jefferson's Capitol than Mecklenburg County courthouse ...." The 1900 brick clerk's office, now attached to the courthouse, is also painted white. This building, of standard state design for clerk's offices at the turn-of-the-century, has lost its central tower and gained a portico.

The courthouse's principal entrance is in the central bay under the portico. Other doors are situated in the central bays of the sides. The dominant feature is its Ionic portico with plastered brick columns with wooden capitals featuring angled volutes. The modillion cornice is carried around the entire building. The classical details were probably taken from The Young Carpenter's Assistant by Owen Biddle.

Susan Bracey's Life by the Roaring Roanoke offers several examples of Civil War-era court cases, which took place at the Mecklenburg County Courthouse. For example, on page 280 and page 281, Bracey cites the case of "Sam, a slave of John H. Winkler", who not long after the war's outbreak, was brought to trial for plotting an insurrection. According to the deposition of one of the witnesses, Robert A. Adams, "on a Sunday in April 1861 [probably very soon after the attack on Fort Sumter] at the residence of Sally Adams" he heard Sam say:

"... that I suppose we will all be free pretty soon, -- I replied that I did not know. Oh yes, he said from what I can find out, Old Lincoln is coming down the Mississippi river and will free everything as he goes--and I think that if we be pretty Keen we will get our freedom too--that he heard that four or five hundred negroes in South Carolina had volunteered their services to go to fight for the South--and he said if he had his way with them he would cut all their heads off and he said that if his master were to tell him that he had to go to fight for the South that he would not go, and that if he had to fight it would be a different way to that, that most of the white folks thought he was a fool but that he had as much sence as most of the white folks and had as good leaders--Mrs. Adams told him that he had better hush talking and he replied that if they prosecuted him, they could not prosecute all that were left behind--that he knew there were no negroes in his district that would join the South--that if he could get his wife and children free at Tom Jones' he would be satisfied--he also said that if he could see every Southern man's head cut off, he would not put his hand near to save their lives--he also asked me if I would fight against the North and I asked him what was that to him and he muttered some words as he walked off which words I did not understand--in all of this conversation the prisoner spoke as if he was in earnest he did not appear to be at all under the influence of ardent spirits."

At his trial, Sam was found guilty and was sentenced to "be transported and sold beyond the limits of the United States ...."

Bracey also cites on page 281 the case of Henry Kinker. Early in May 1861, soon after Virginia seceded in April of that year, Kinker, a white man, listed on the 1860 census as born in New Jersey, and working as a farmer in St. Tammany (now Bracey), was arrested for having been "since the first day of January 1861 ... using incendiary language calculated to militate against the peace and good order of the Commonwealth ..." Bracey elaborates: "He had stated on one occasion that he 'wished that the State of Virginia might be over-run by the north and the slaves freed, in order that every one might be forced to work for himself ...'. He further stated that there was no General in the South under whom he wanted to fight. The case was dropped in May court."

Another similar court case, cited by Bracey on page 281, is that of William G. Rook. Rook, a white farmer, living in the Forksville area, had been arrested for slandering the institution of slavery. A witness stated that Rook had said that "the owners of the slaves ... have not the right of property in the said slaves", declaring and saying to others that he did not believe slavery was right and "that a man had the same right to sell his brother as to sell his slave in bondage ...." The disposition of this case was delayed until November of 1862 when Rook was declared not guilty.

On page 287 Bracey refers to the court's involvement in the war effort with the county issuing small denomination paper currency: "On May 19, 1862, the Mecklenburg court ordered the issuance of paper currency to be used toward 'arming and equipping volunteers ... and supporting the families of those who are indigent and in service ...'. The bills were to total $20,000 and were to be issued for amounts of one dollar or less ($.75, $.50, $.25). They were to be backed by faith in the county of Mecklenburg. The clerk was to have the printing done and was to employ J.J. Daly and S.R. Johnson to assist him in signing and numbering the bills. (The clerk was also to keep a record of the amount and denominations that were issued.) Once this was done, the clerk was to exchange these notes for 'current Bank notes' and turn this money over to J.J. Daly, as 'agent, treasurer and receiver for this County'." Each currency note included the following: "The Property real and personal of the people of the County bound for payment. The County of Mecklenburg, Va will pay to the Bearer ... according to the Act of Assembly passed March 29th 1862."

On page 420, Bracey refers again to the court's involvement in the war effort and its arrangements for medical care for soldiers: "In November Dr. John W. Williamson was ordered by the court to tend to soldiers; Samuel G. Johnson, E. Binford, Thomas C. Reekes, William H. Gee, James T. Walker, and James McCargo were to assist. In July 1863 E. A. Drumright was appointed a commissioner to visit the sick and wounded. In June 1864 Dr. William H. Northington was so ordered."

Bracey also refers on page 287 to justices in December 1862 "confronted with a new problem; they received their first order to impress slave labor to work on constructing fortifications (first at Richmond, later at Petersburg)." Bracey continues: "The first such draft of slaves in the state had been made two months before this. The practice continued through the remainder of the war, not always without opposition." Bracey explains that the continued drafting of slaves for this work often caused considerable hardship to their owners. She refers to "... widows in Mecklenburg who had large families and other dependents to support and had only one male slave and no white male to help them." She refers to an anonymous Mecklenburg citizen, who brought the problem to the attention of the Governor in a letter, signed as "A friend of Justice, and received February 23, 1864. This letter indicates that there were two such women in a neighborhood, who, if deprived of their males slaves during the planting season would be in dire circumstances. Bracey indicates that the letter writer "... felt it would be better for everyone to exempt such women from the requirement of sending slaves." The anonymous author, exhibited an unfavorable perception of members of the judiciary, writing: "This matter should not be left to the entire control of magistrates, some of whom are too sordid and selfish to act justly toward all."

Bracey continues referring to the Mecklenburg court's war effort on pages 287 and 288, noting that in December 1862 the court appointed a Special Police and a patrol and that a few days later, it appointed Thomas F. Goode, "now retired from the service, as a commissioner to attempt to procure from the Governor 'a small quantity' of ammunition to be used by the county 'in cases of emergency'."

Bracey also refers on page 289 to the county court's recommending in the later years of the war the exemption from the Confederate government's draft of people whose jobs were considered vital to the war effort. She refers to Robert H. Bugg's exemption, requested in September 1864, noting that he "... then was county agent for providing for indigent families, and the court believed him to be more valuable to the Confederacy at this job than in military service." Others requesting exemptions were O. Robertson, a tanner, and Amos G. Pool, who ran an operation where implements for "carding wool" were manufactured. Several mill owners like John P. Hudson and George F. Griffin, also requested exemptions at court. Bracey also notes on page 290 that "mill produce was, under a contract, sold to the county agents whose job it was to provide for the families of the poor soldiers." She continues on page 290 and page 291, referring to the increasingly precious commodity of salt, noting that Mecklenburg's war-time salt supply was "obtained through court-appointed agents" like J. J. Daly, "who contracted with the officials at the salt works or with state officials." She also refers to other commodities like "Cotton Yarn and Cotton Domestic" that the county obtained through court-appointed agents for distribution. On page 291, Bracey notes that in July 1863, Thomas C. Reekes was appointed to get cotton articles from North Carolina "for the immediate relief of the people in his neighborhood."

A particularly unfortunate war-time court case, cited on page 237 of Bracey's book is that of John Garner, a "free man of color", who was tried in October of 1864 for breaking and entering and theft. He was found guilty and was sentenced to be "sold into absolute slavery."

References to these war-time court cases and court documents are made possible by the fact that unlike some other county courthouses, Mecklenburg's was spared from destruction during the war. Intense military activity during the Civil War suffered losses of many southern court records, due to ransacking, including fires set by Union troops. By May of 1864, Mecklenburg citizens were becoming increasingly aware of the very real possibility of an invasion. Page 293 of Bracey's book, citing Mecklenburg Order Book No. 7, page 550, indicates: "On May 16, the justices ordered the clerk to 'remove the records and the papers from the Clerk's office to someplace of safety when he or the Presiding Justices shall deem the same in danger of being injured by the public enemy'."

Many of Mecklenburg's Civil War era court documents can be found at the historic courthouse, which is set in a shaded square, surrounded primarily by nineteenth and early twentieth century commercial buildings. Late nineteenth century courthouse square activities were reported as follows in the March 3, 1893 edition of the Boydton newspaper, The Midland Express:

"Court day always brings a full attendance. Last 'court' was no exception to the rule. People began to arrive early in the morning on foot, horseback, in carts, wagons and every other imaginable conveyance. Patent medicine men, sewing machine agents, nursery men, horse traders, and everyone under the sun who had something to sell was present and endeavoring to dispose of his wares, but trading was not very brisk especially in the horse line."

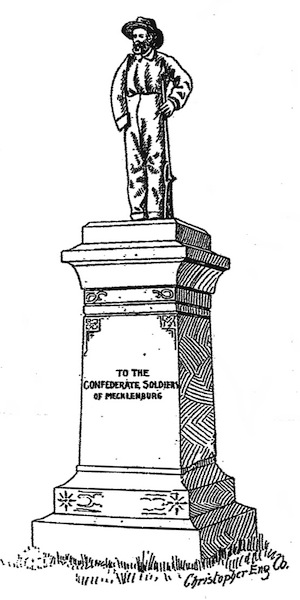

A Confederate monument, erected by the L. A. Armistead Camp, Confederate Veterans, stands northeast of the courthouse's main entrance on courthouse square. It was dedicated on August 7, 1908 and rededicated, thanks to efforts by the Armistead-Hill-Goode-Elam Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp No. 749, on November 2, 2002 after a restoration. Initially, the monument consisted only of a granite base. The bronze statue, subsequently added atop the monument, is reportedly based on John Bowen, of the Third Virginia Cavalry, who lost his arm at the battle of Yellow Tavern, in May 1864. Bowen reportedly used a ladder to ascend to the top of the monument's base and stood with empty sleeve, old cavalry hat and musket by his side, and let the artist in attendance photograph him. The resulting statue of the soldier was initially positioned facing the courthouse, to indicate his loyalty to the county. For years the statue was able to be swiveled on the base, and it is reported that for many decades on Halloween, kids used to turn the statue 180 degrees, and the soldier would face that way until the next October 31 when he would be reversed. When the monument was refurbished, a professional restorer fixed the statue so that it could not be turned. At that time, it was decided that since the soldier was carrying a musket, he was obviously on picket duty, and therefore he should face toward the enemy, or away from the courthouse. The statue is seven feet tall, weighs 1,600 pounds, and originally cost $1,000 to have made, delivered, and set in place. The monument's granite base is twelve feet high and cut with these inscriptions: "To the Confederate Soldiers of Mecklenburg", "From Bethel to Appomattox"; "1861-1865".

In 2009, while the historic courthouse was under renovation, NFL Hall of Fame running back and 2006 Dancing with the Stars champion, Emmitt Smith, visited the county's circuit court facility, located then at 1294 Jefferson Street (now home to the Boydton Public Library/Southside Regional Library Headquarters), while filming Season 1, Episode 2 of the television show, "Who Do You Think You Are?". Tracing his family tree with the help of local historian John Caknipe, Jr., Smith accessed the 1826 deed wherein his fourth-great grandmother, Mariah Puryear, was listed as a young slave girl, originally belonging Mecklenburg's Samuel Puryear. Smith was particularly moved by the coincidental fact that this deed came from Deed Book Volume 22, as his former football jersey number was 22. He learned through the deed book that Samuel Puryear gave a "negro girl named Mariah", approximately 11 years old, to his daughter, Jane, along with a horse bridle and saddle. Eventually Mariah was passed on to Jane's brother, Alexander, a slave trader, who, while born in Mecklenburg, lived a portion of his life in Monroe County, Alabama, as did Mariah. While in Boydton, Smith learned more about slave trading. He also learned that it is believed that Mariah was Samuel Puryear's daughter; thus making a slave-owner most likely Smith's fifth-great grandfather. Smith eventually found some comfort in learning that after Emancipation, Mariah was with all of her children. He also remarked on how Mariah was smart in naming her first child Mary, after Alexander's wife, likely to remind the Puryears, that she was part of their family.

Contributor: Leigh Lambert, Director of Southside Regional Library

Websites:

http://www.mecklenburgva.com/circuit-court.aspx

http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/circuit/Mecklenburg/home.html

http://www.oocities.org/mecklenburgscvcamp1624/monument.htm

Sources:

Full Sources for Historic Sites [pdf]

http://www.mecklenburgva.com/circuit-court.aspx

http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/circuit/Mecklenburg/home.html

http://www.oocities.org/mecklenburgscvcamp1624/monument.htm

Sources:

Full Sources for Historic Sites [pdf]

(c) Copyright 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by Jason Winter ||